By Júlia Lopes, Juliana Sousa and Maria Beatriz Giusti

Brasília Newspaper/Agência Ceub

April brought a cold autumn in 1964, when 50 armed soldiers invaded Rosa Cimiana's home. She was just over 4 years old.

Strengthened by laws they were unfamiliar with and by a newly established regime, the men in uniform looked for what was, according to them, a criminal with a high level of threat to the government.

The man was her father, Arthur Pereira da Silva, accused of being a subversive

Arthur was a father of four children, a railway worker and a member of the Communist Party, the so-called “Partidade” in the city of Santa Maria (RS).

Rosa remembers the day her father was arrested and the brutality of the soldiers.

“I remember it was very cold, I hate the cold to this day because of that. That day, the military destroyed my family's house looking for the 'Gold of Moscow'. There were 50 men to catch my father. My father never agreed to pick up a weapon, he wouldn’t even pick up a pocket knife.”

At Christmas of the same year, through a practice similar to what is now known as the “Christmas Pardon”, Arthur was released.

“I remember it had been a long time since we saw my father, when he came home, we only knew how to celebrate 'daddy, you're going to spend Christmas with us!”.

Arthur's return was the opportunity Rosa's family needed to escape the regime. Very afraid of being arrested again, but not wanting to flee abroad, Arthur lived clandestinely until the end of his life.

“He said he would rather live clandestinely in Brazil than in a country he didn’t know.” says Rosa.

When Arthur had already been living clandestinely in Brazil for almost 15 years, in 1980, he fell ill.

The diagnosis was a very serious infection in the testicles resulting from the torture suffered during his time in prison. Arthur had never told his family about what he suffered while in prison.

Rosa was the only one in the family to know exactly what had happened. In February 1982, Arthur passed away due to the infection.

The fight for the right, the difficulty of forgiveness

“The most important part of the amnesty process is the apology that the counselors give at the end of the process.”

Rosa followed in Arthur's footsteps and also dedicated part of her life to political activism during the regime.

Wanted by the military and arrested “a few times”, Rosa fought for her own amnesty, that of her family and, mainly, that of her father.

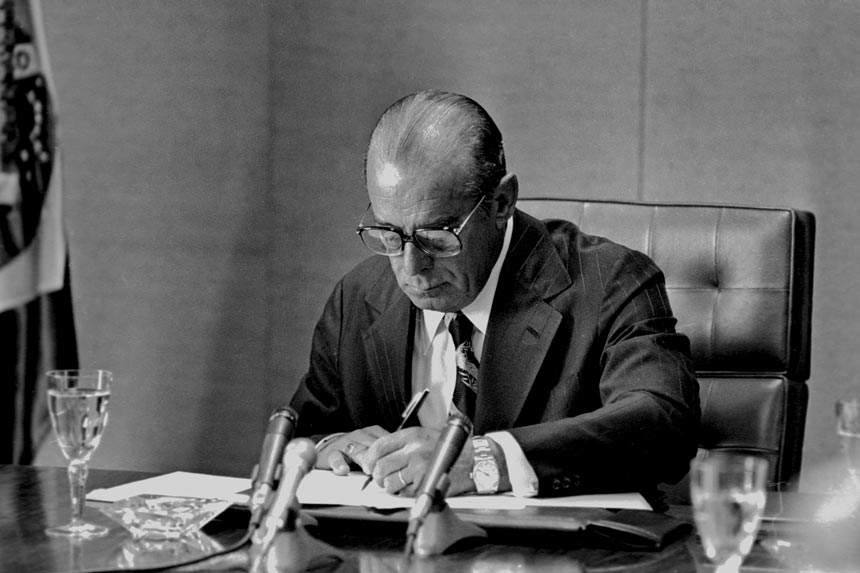

The Amnesty Law, enacted on August 28, 1979 during the government of dictator João Baptista Figueiredo, was one of the solutions proposed at that time to end the dictatorship.

The beginning of the end

For the professor at the Federal University of São Carlos, João Roberto Martins Filho, the end of the dictatorship was planned. “They knew that sooner or later the regime’s power would return to the civilians, so all of this was done so that the end of the regime would be in a controlled manner.”

Rosa, just 20 years old, at the invitation of then deputy Ulysses Guimarães, insisted on being present at the session that approved the pardon for political criminals.

She felt, for the first time, hope that she could get her life back. However, her fight to be amnestied continued for years, but without ever losing its importance.

The amnesty

The Amnesty law granted pardon to political prisoners and military personnel who committed related crimes, any repressive action against politically persecuted people.

“The amnesty served both sides, but that was not the opposition’s intention when they fought for forgiveness”, explains João Roberto. The professor emphasizes that the Law is an inheritance so as not to settle accounts with the past.

Political scientist Alessandro Costa believes that there was no transitional justice.

“A complete transitional justice would involve holding accountable those who, in the name of the State, tortured those they were supposed to protect.”

For Costa, the population had to swallow the Amnesty Law, which pardoned both sides, to put an end to a greater evil that was the dictatorship.

Amnesty after death

Arthur Pereira da Silva was amnestied in 2003, 21 years after his death and 39 years after his first arrest.

Rosa tells, with great emotion, what it was like to hear her father's amnesty sentence.

“Hearing the forgiveness was like I was back at 4 years old, living in my quiet town. No matter the money, no money will pay for what my family and I went through. My pain is for the rest of my life. It’s a brand that will never go away.”

Supervision: Luiz Claudio Ferreira